Storytellers of NVR 1.1

Poems by Jonathan Chibuike Ukah, Thomas Alan Orr, Mattie Quesenberry Smith, and Marly Youmans

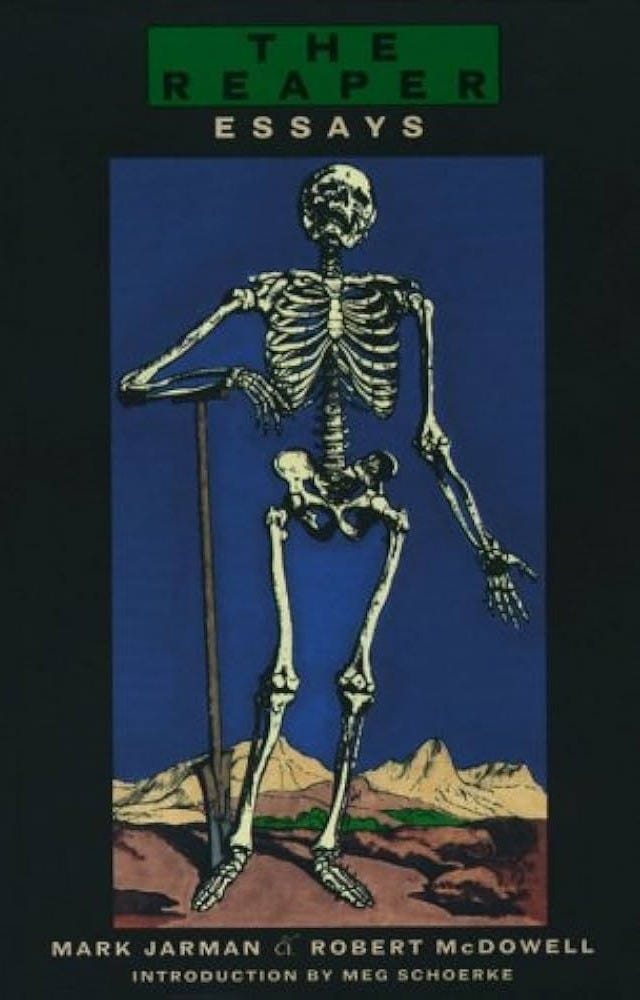

Recently, while perusing a bookstore in Roanoke, Virginia, I came across a volume of the collected manifestos and polemics that Mark Jarman and Robert McDowell published in The Reaper, an influential journal of narrative poetry they edited during the 1980s that featured poets such as Jared Carter, Rita Dove, and Dana Gioia. This felt like a case of the book finding its reader. While I am not as polemical as Jarman and McDowell, and while my logo of someone reading under a tree is not as menacing or as cool as the varied Grim Reapers that adorned their journal, I nonetheless founded New Verse Review in part to carry forward a similar mission. I want to promote the longish narrative poem. That is not the exclusive goal of NVR, but it is why the subtitle specifies it as a journal of lyric and narrative poetry.

Below are four of the longer narrative poems from NVR 1.1. (You can read the full issue here.) As a preface to them, I include this quotation from Jarman and McDowell’s essay “The Elephant Man of Poetry”:

What does The Reaper mean by a poetry with a narrative focus?…The poet must make sense of a situation that is troubling him and say it to someone else; the reader needs to make sense of the world, which troubles us all….Only when the story as a whole becomes a metaphor does this understanding [of our lives and the world] occur.

Without further ado, here are four long narrative poems from NVR 1.1 in the order that they appear in the issue.

“Easter” by Jonathan Chibuike Ukah

I arrived at the Nnamdi Azikiwe airport, searching for the body I left behind; I guess I packed it in one of the bags which I gave to my family for Easter. I spent years marooned in Germany, trapped within the shadows of a war fought where words grow feathers to perch into ears addicted to old ways. I’m willing to tear off my clothes, spread out my wings in the thick air and go with the cold, unrequited sacrifice like a bird chirping in a night’s thunderstorm. I would not be without warm clothes, Emeka and Okoro were as tall as I was, schooled in the recent fashion trends, and blessed with a taste like a swan with the grace of gliding like kings, screaming of life and colour into a grave. We wore one another's clothes before I left. I’m happy things looked like summer here. The arrival terminal was a marketplace; I saw an elderly man bearing a placard, Ifeanyi's Junior Uncle. My smile hung on my lips like a lipstick to slaughter the cold of the Harmattan. After twenty years of tottering abroad, I remember I did not have a junior uncle. The man’s moustache reminded me of Emeka. Welcome to Nigeria, Brother. I followed him to a waiting car at the car park, where Okafor, unchained to the teeth, hunched over the steering with a whale face, smiling like the sun on a resurrection day. Please, give me your suitcase, there are thieves here. Emeka smiled at me and made a cross sign. I knew his parent were Catholic in the days. You will need rest, then food, and sleep. I wondered if growing into a manly mother was part of a man’s masking of virility. I will drive with tenderness, like in Obodo Oyibo. Okafor's teeth were so white and sparkling that the car was in a swamp of a white halo. I smiled until we arrived at the hotel. Emeka held the door for me like a butler. Brother, be careful here; give me your valuables. He didn't wait for me to hand them over but snatched them with my wallet and suitcase. The reception was, as you might say, warm. I emerged from the shower naked and walked into an empty room. My two bags had disappeared. I stared around the room, and there they were, Emeka and Okafor pointed a gun at me. With a grin. With bolted eyes, stale crust, like an oyster on a saucer of wriggling worms. We have waited for this day, Brother, but today, you must die for all of us to live. Their laughter sliced a hole in the hotel floor. I stared at my brother, whose beauty was so pure that mad men suspended their ravings temporarily, until the last glimpse of his shadow lived no more. That’s how the kingdom suffers violence, and the violent taketh it by force, the Iroko tree falls and crashes another Iroko; the rose collapses and crushes another rose, the flower war is the clashing of beauty and grace, against the ploughing of the spirit, the reaper, yet the Bible is the book that matters most, tucked under their gun-bearing armpits, read with hands clutching knives and bullets, in a land where great trees fall, rocks shudder, the smallest of flowers cower in silence, though they lie far from the maddening crowd, where even elephants lumber and launder safety. The black iris of my brother’s bloodshot eyes told me there is no Jesus resurrecting in light air, and the tombstone does not roll away in time.

Jonathan Chibuike Ukah is a Pushcart-nominated poet from the United Kingdom. His poems have been featured in Ariel Chart Press, Atticus Review, Zoetic Press, Unleash Lit, Down in the Dirt, and elsewhere. He won the Voices of Lincoln Poetry Contest in 2022 and The Alexander Pope Poetry Award in 2023. He won the Unleash Creatives’ Editor’s Choice Prize in Poetry in 2024 and was shortlisted for the Minds Shine Bright Poetry Prize in 2024. His poetry collection, Blame the Gods, published by Kingsman Quarterly in 2023, was a finalist at the Black Diaspora Award in 2023, as well as the Grand Winner of the Wingless Dreamer Poetry Prize in 2024.

“Crop Duster” by Thomas Alan Orr

Like sentries, maples flank the narrow lane that curls past corn and beans across the bridge. A rusty gate hangs by a single hinge. The barn stands on a swell of land behind the brick foundation of a house long gone. A grassy airstrip running from the barn three thousand feet is overgrown with weeds. He steps out of a rusty trailer, smiling, to greet the ag reporter keen to learn a bit about crop dusting with a plane. A lean and grizzled man, he has a limp. “I’m slow,” he says. “And that’s a story too.” They swing the barn doors open, stepping in. The sun through cracks illuminates the dust and glances off the windshield of the plane, a Piper Pawnee, made in ‘sixty-six, a single-engine, low-wing, prop-driven craft. He brushes dust from off the fuselage, revealing “Queen Bee” painted there in red. “We called ‘em dusters back in the day, but they go by aerial applicators now. Ask me, it ain’t so colorful, know what I mean?” He spits some chew and laughs. “Been doin’ this since I was just a kid but not much now. My age is catchin’ up! How it works is first you lay down smoke to see which way the wind is blowin’. Then come in low about eight feet above the field to dose the crops and pull up fast to miss the trees. You gotta be alert! When I was in the air we worried most about the power lines. You’re flyin’ low and hit one at a hundred miles per hour and it’ll cut your plane in two. No lie! And now there’s towers and windmills stuck in the middle of farmland everywhere!” He pauses, gives the plane a winsome look. “Good days, the Queen and me, we danced up there. She never failed. My first old duster crashed. A ground thermal turned us upside down. I crawled away before it blew apart. My leg was broken bad. That’s why I walk like this. God’s ways are strange. My wife died young, but I survived the crash to tell about it now. Things happen flyin’ low like that. I heard a guy got killed in Arkansas. Two dusters hit each other in the field. It kinda makes you think, but then you do stuff anyway despite the risk, you know?” “The boy was tellin’ me about a strain of marijuana called Crop Duster. Hell! At least it ain’t called Aerial Applicator!” He laughs again, his chew refreshed. “What’s that? No, haven’t tried it. Used to take a shot of bourbon when the Queen and me went up. I’d probably lose my license now. It won’t be long, I guess, before the drones take over. Then old boys like me, well, we’ll be done. The Queen? I s’pose she might be fighting prairie fires somewhere out in North Dakota or Saskatchewan!” He blinks and thumbs his eye. “It’s just the dust!”

Thomas Alan Orr raises Flemish Giant rabbits on a farm in Indiana. His most recent collection is Tongue to the Anvil: New and Selected Poems. His work has been featured on Garrison Keillor's Writer's Almanac. He has work forthcoming in the Merton Seasonal and the Midwest Quarterly.

"A Slice of the Apocalypse” by Mattie Quesenberry Smith

For Hal

You hang at the edge, knee deep in splash,

Fly-fishing a summer of remarkable pools.

If overhead, the cosmos unspools, what of it?

It’s between you and Falling Creek,

You, knee deep in atmospheric want.

If it is a remarkable summer, you don’t notice,

But for the tug and tight race—a rainbow

Fit for two hands, ready to reel.

If it is a remarkable summer, wouldn’t the stars have told it

The night before—glowing down summer’s ceiling,

Somehow mapped by the Milky Way?

You take time to land the rainbow, while apocalypse

Slices the air, and a car crashes through,

Rolls six times while you land it.

You unhook the fish—a rainbow of surprise—

As the car slides to rest, and the screaming begins.

You find her first, thrown yards from the wreck;

And the little boy, he is crawling out of the broken window.

You and a friend guide the driver up the bank,

And he is slapping his bare chest for cigarettes,

“I need a cigarette,” he says with alcoholic breath.

The boy cries, but you tell him he’s alright, and the woman is, too,

Saved from the half-spun wreck. The story can’t get any better

Than that. They are carried away, and no one in his right mind

Would follow them into the future weather where

Apocalypse slices summer, and Heaven’s split belly spills its guts

In an abundance of ways, leaving you with a trout, stolen and released;

A hook, cast and recoiled; iridescent catastrophes, lit and dispelled.A Ph.D. candidate who studies critical reflection and critical reflective writing in Integrative STEM Education at Virginia Polytechnic and State University, Mattie Quesenberry Smith is an English, Rhetoric, and Humanistic Studies instructor at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia. Her poetry has been published in several journals and anthologies, such as Tupelo Press’s 30/30 Anthology, The American Journal of Poetry, Intersections—Poetry with Mathematics, and Phi Kappa Forum.

“Saint Thief” by Marly Youmans

Once there was a set of bones so white And smooth, so seeming pure and radiant That even the most corpse-abhorring man Called them beautiful. Few people knew To whom the bones belonged, although I do: The bones belonged to a thief. He was caught And hanged above long grass at a crossroads, And as he struggled in the air he thought Of his good wife and their one living child, And then he died as his legs ran and ran As though he could escape and go to them. His flesh dripped like the rain, and fell away Under the summer’s steady glare of sun And cold eye of the moon. The gibbet fell. A riot of wildflowers mobbed the grass And pleased such passers-by as still retained A childhood gift for seeing miracles. One day a peddler waded into blooms And spied the bones of the thief and, finding them Strangely pure and sparkling, collected them. For, he thought, if nothing else, they’d make The finest bone meal for his garden soil. For years they lay in a rough hair-skin bag In the peddler’s shed, although a single bone Was bartered to a neighbor for a hen, And then was pierced and bored to make a flute. The notes it gave were just as fair and fine As bones that slept undreaming in the bag, And signaled a new sweetness in the days Of spring and summer to the clustered shacks— Song marking tranquil weather, when the girl Who owned the flute would play her melodies After all her household chores were finished. Even the lightest songs upon the flute Could bring on tears, and yet the people loved To hear, and were the better for the hearing. Eventually the bone-hoard peddler died, And all his goods were gathered in a heap And sold to a dealer from the city’s core. One day, on hearing that an embassy Commissioned by the church was hunting here And there for bones of a particular Saint stoned to death a century before, He recollected the hair-skin bag and bones, And followed the procession of the priests And noble lady who were scouring hill And hollow for the saint’s mislaid remains. And he had great good luck because the bones Were bright and polished, as if they were formed From moonbeams, so that the assembled priests And the lady in her silken garments Cried their surprise when light spilled from the bag, And soon their hearts were moved to find the bones Of the thief to be the bones of the missing saint. The bones were smashed and scattered then, to live In far-off lands and with a foreign name, Venerated by poor and rich alike, Dressed honorably in silver or in gold, Given reliquaries in shapes of arm Or foot or star or castellated fort. Even royals bent the knee to the thief. Even grandchildren of the thief knelt down To cross themselves and sigh before his bones. Now when the thief had been gone from this world For many years, and many thousands of prayers Had been implored before his dry remains, The bones at last began to work their wonders: Three prisoned girls were healed of leprosy; A barren queen conceived and bore an heir; Some sailors wrecked at sea came bounding home; A sexton heard a faint, heart-rending tune That drifted from a reliquary arm, And myriads detected a halo Of moonshine ringed around a finger bone: In death, the thief had shanghaied miracles. The upshot of furor and pother meant Angelic beings of the Divine Council And God on his chariot throne in Heaven found A thing or two to say about the thief. An angel spoke who’d passed the very spot Just when the thief ran helpless legs on air. An instant or a day or a thousand years Fled away as they mused as one on all The fume of words that floated up from those Who begged the thief to intercede with the Lord. I know about the scattering of bones, I know about the thief running on air: I’m the singer and the storyteller. But did the thief burgle the hearts of those Who bent near bones in love, and did he creep Underneath the wing of the Lord Most High In his daring boldness? And did he steal That infinite and uncreated heart? Or did bones change, swaddled in the richest Prayers of the needy? And did the thief Himself transform, the spillikins and crumbs Of his own bones singing to his spirit? That I can’t tell you. That you must decide. As for the rest of it, this much I know: The girl who ruled the flute bequeathed the gifts Of song and story to her kin, and her Children to their children; my very own Great-grandmother then told the tale to me When I was young. And here am I, grown old, Tossing its strange, glittering pinch of truth And enchantment into the air and time.

Marly Youmans is the author of sixteen books of poetry and fiction, including her most recent long poem, Seren of the Wildwood (Wiseblood Books), her latest novel, Charis in the World of Wonders (Ignatius Press), and her newest collection of poems, The Book of the Red King (Phoenicia Publishing.) www.thepalaceat2.blogspot.com