Limiting Poetry's Feedback Loop

On Writing Poems for People in the Real World

Editor’s Note: Here’s a bracing polemic from Steven Searcy. You may think his criticism of self-referential poetry is too stringent. (I like a lot of poems about poetry, and I suspect my own poems are at times caught in the feedback loop.) But it is important to write for an audience that isn’t just other poets. So give Steven’s essay a fair read and then share your thoughts in the comments!

An insidious tendency permeates contemporary poetry. The trouble is self-evident, but it can be easy to miss when immersed in the “poetry world.” Words and workshops, reviews and teachers, anthologies and famous poets persistently appear. Being a writer takes on undue significance. Excellent poets are not immune, and the problem occurs across many styles, though it seems especially prevalent in poems with a direct and laid-back tone, and naturally in poems that break the fourth wall. Examples abound, though in fairness I’ve aimed at bigger names. These poems are not necessarily “bad,” but are presented as specimens of an excessive proclivity.

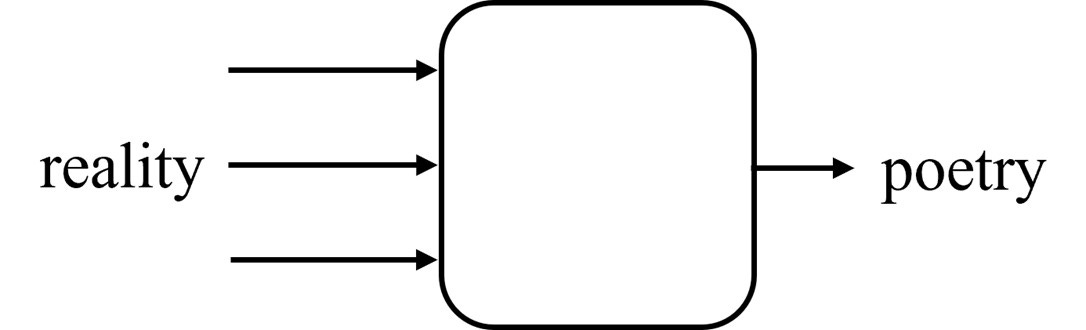

To illustrate this predicament, consider a block diagram representing the poem-creation process. This is overly simplistic and mechanistic, but let’s use it as a working model for discussion. The inputs are various aspects of the reality of life in the world, which are transmuted into poetry.

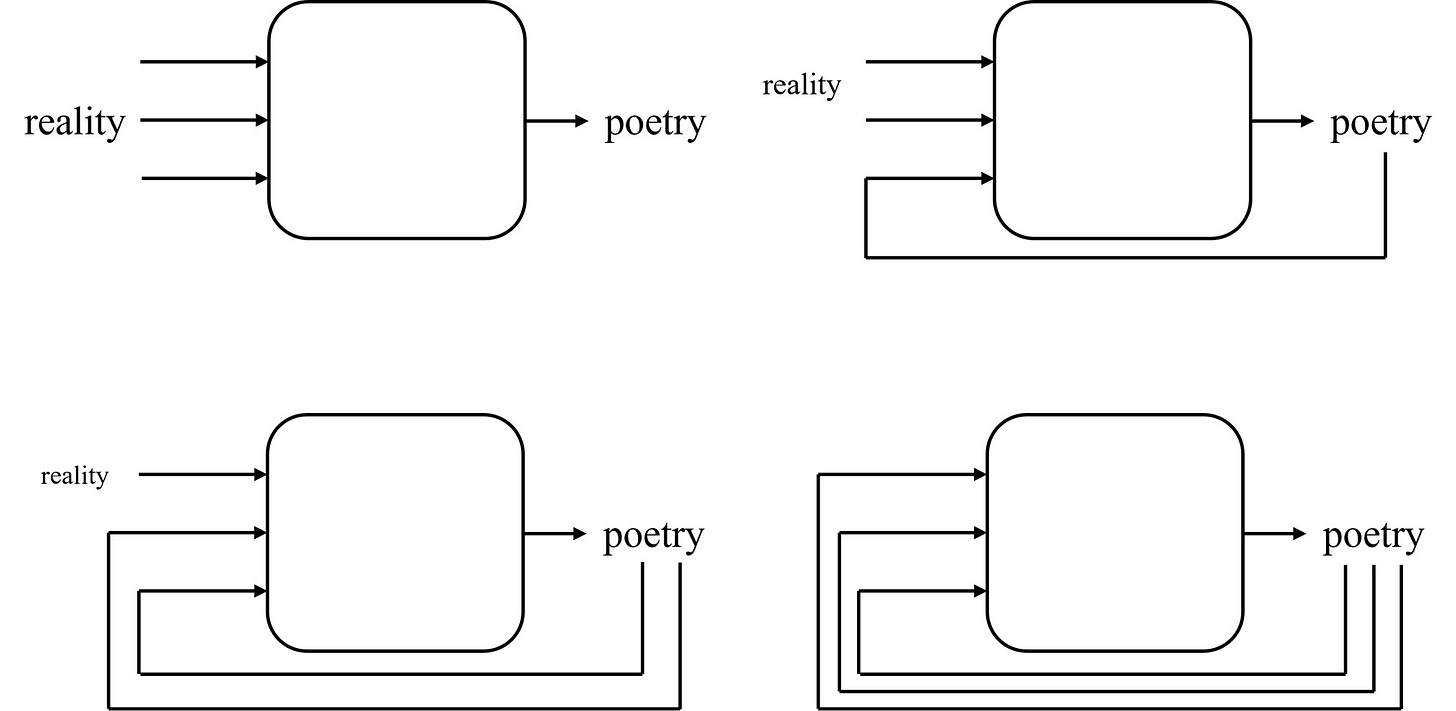

The problem at hand occurs when the process is adapted to include feedback, meaning that poetry becomes a direct input for the production of new poetry. Left unchecked, the entire operation can degrade into a self-recycling closed loop—that is, poetry becomes less and less concerned with existential reality, and more and more concerned with itself.

Poetry is, of course, a part of reality—but only one small part. Poetry consumes an abnormally large slice of the poet’s experience, even compared to well-educated, literary-minded readers. With unmitigated feedback, poetry becomes increasingly self-focused, inevitably alienating most people who are not poets or voracious readers of poetry. Perhaps “poetry makes nothing happen” when poetry is so often concerned with memorializing great poets or pondering its own nature?

This is not a new issue, but is one distinctive feature of contemporary poetry’s decline—perhaps both a cause and a symptom. Dana Gioia’s 1991 essay “Can Poetry Matter?” incisively diagnoses how poetry has become a subculture: “outside the classroom […] poets and the common reader are no longer on speaking terms.” Wendell Berry’s 1975 essay “The Specialization of Poetry” examines the problem of “specialist-poets” with their “doctrines […] of the primacy of language and the primacy of poetry,” maintaining that “the subject of poetry is not words, it is the world, which poets have in common with other people.” Berry draws heavily from Edwin Muir’s 1962 The Estate of Poetry, where Muir warns of “the temptation for poets to turn inward into poetry, to lock themselves into a hygienic prison where they speak only to one another, and to the critic.”

Producing a new poem can be thrilling, but this does not justify indiscriminate composition. David Yezzi has written that a poem’s “bid for universality” consists of its “language, the degree of truth it achieves in describing experience, and the greatness of its subject matter” (emphasis mine). Here, Yezzi is discouraging political didacticism, which “runs the risk of seriously limiting a poem’s relevance outside of the finite context of a given issue or debate,” but the same may be said of poems that focus on poetry. Such work distances itself from general readers who want poets to give voice to meaningful experience but are uninterested in the experience of being a poet.

Now to acknowledge some likely objections. Poets since antiquity have written great poetry about poetry, from Horace’s Ars Poetica to Pope’s Essay on Criticism to well-known modernist works by Marianne Moore and Archibald MacLeish. Throughout the tradition we also find invocations of the Muse and overt references to the poet composing the poem, but these are ordinarily opening or framing structures, not the main focus. This is not to say that all poetry of the past is free from the problem of swollen self-reference, but the issue is particularly pronounced and vexing today, as poetry’s audience has narrowed considerably.

Poets think often about the poems they love to read and the poems they are writing, and many even teach creative writing vocationally. Since the art of poetry occupies a prominent place in the poet’s life, there is a propensity for feedback loops to become habitual. The cherished book of poems on the nightstand becomes a prop in a poem. Technical elements such as enjambment and caesurae are mentioned directly or used as metaphors. The pen and paper are recurring images in the poet’s oeuvre. Unconstrained feedback loops lead poetry deeper into Muir’s “hygienic prison,” confined by its own devices, woefully incurvatus in se, and (mercifully) isolated from the rest of the world.

At the risk of offending many and damning myself, here are some guidelines to help limit poetic feedback loops (though as with any rules, there will be exceptions):

Each poet may publish one ars poetica lyric poem in his or her career. (There are no restrictions on prose essays and books, verse essays and epistles, etc.)

For each published collection, a poet is entitled to publish at most one poem that explicitly mentions the act of reading or writing poems.

Any poem that specifically concerns writing or poetry should offer something valuable to readers who are neither writers nor immersed in a literary lifestyle, or should be clearly framed as an address to fellow poets, critics, academics, etc. (acknowledging the poem’s limited scope).

Any line(s) of poetry quoted as an epigraph should enhance the poem and should be subservient to the poem (not vice versa).

So-called “After” poems (quoting or riffing on a poetic line or style) should be used sparingly—no more than once per collection—and should vindicate their existence as original poems, rather than personal expressions of admiration. (Poets who admire a particular poet or poem would in many instances be better served by writing critical prose.)

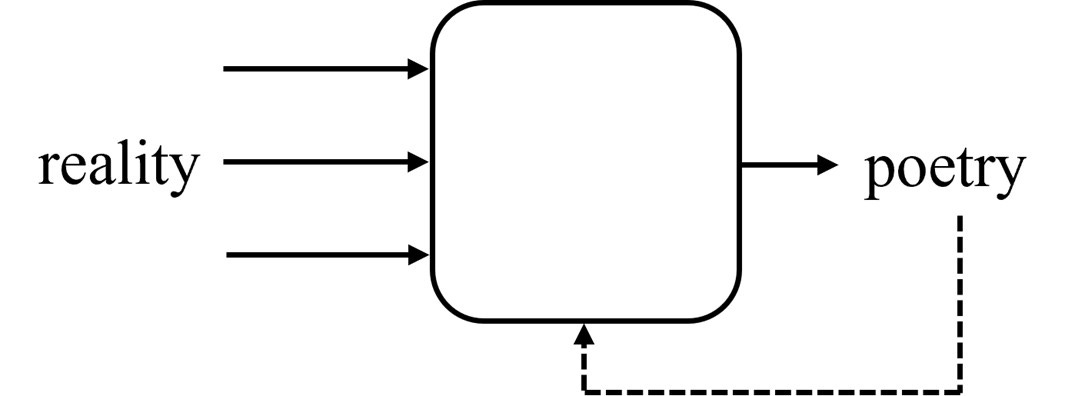

Is the poet then to abandon reflection on the creation of art and disengage with poetic forbears? Certainly not! New work will usually be enriched by aesthetic contemplations, just as many systems benefit from appropriate feedback. The key distinction is that these must be recognized and mediated as secondary inputs to the poetic process, which guide and refine the primary operation. In this way, the poet’s experience as a writer and appreciation for the tradition can inform his writing but need not proceed directly into the content of the poetry. We can represent this moderated feedback as a dashed line entering from the side as an ancillary input, while broader reality remains the primary input.

There are places for knowing self-reference—one thinks of the paintings of Magritte or other conceptual art. This type of work can challenge and amuse, but will most interest other practitioners and critics, and should be anomalous, lest the art form degenerate into a self-serving cul-de-sac. More importantly, involuntary self-referential tendencies must be identified and strongly limited if poetry is to have any hope of escaping its insular dungeon.

For poets who seek a meaningful and lasting connection with a wide range of readers, it would be worthwhile to step outside poetry “bubbles,” engage vigorously in shared reality, and remember that poetic feedback loops should be carefully regulated. A house of mirrors is a nice stop at the annual funfair, but not so fun to visit frequently—and certainly no place to take up residence. Caveat lector. Caveat scriptor.

Steven Searcy is the author of Below the Brightness (Solum Press, 2024). His poems have appeared in Southern Poetry Review, Commonweal, The Windhover, Blue Unicorn, Autumn Sky Poetry Daily, and elsewhere. He lives with his wife and four sons in Georgia.

This is a great article, and a bit of a hobbyhorse of mine for the last few years. There's something about self-referential poetry that reminds me now of a vacuous essay written to appeal to the markers.

Excellent work, Steven, and in under 1200 words! I'm so glad you wrote it. This does have me thinking though: How do you imagine your argument would apply in a culture (which, to be fair, I do not think truly exists, currently, anywhere in the world) like that of, say, Tang or Song Dynasty China (and later) or Edo Period Japan, where the poets are constantly writing to and referring to each other and to the act of writing poetry as well as constantly referencing or copying the other masters' poems and expecting their readers to know this, and yet this poetry is very much so to an audience, and was largely loved by the people and still is to this day? I need to think this through for myself (especially as I am engaged in projects on those subjects), but I am also curious what you think. I guess it probably has to do with the culture in which the poetry is being received.