By Carter Davis Johnson

I was swallowed by granite, trapped within the ribcage of cold grey stone. Even with my thin frame, I was barely able to move within the secret passage of Hawk Tower. Behind a wall in his wife Una’s second-story room, Robinson Jeffers built a small winding staircase that descends to the ground floor. Because the bottom door was shut, the bend in the stairs was completely dark. I twisted my shoulders, ducking my head and trying to achieve a successful physical geometry. The toes of my leather boots scuffed against the sides. Suddenly, while in the middle of the turn, a sensation flashed within and around me. I felt disorientated. Perhaps it was claustrophobia, but that seems like too strong a term. It only occurred for an instant: the instinct to escape, the barely conscious wordless prayer for deliverance. Then, as suddenly as the feeling arose, I turned the corner and moved toward the soft light at the stair’s threshold.

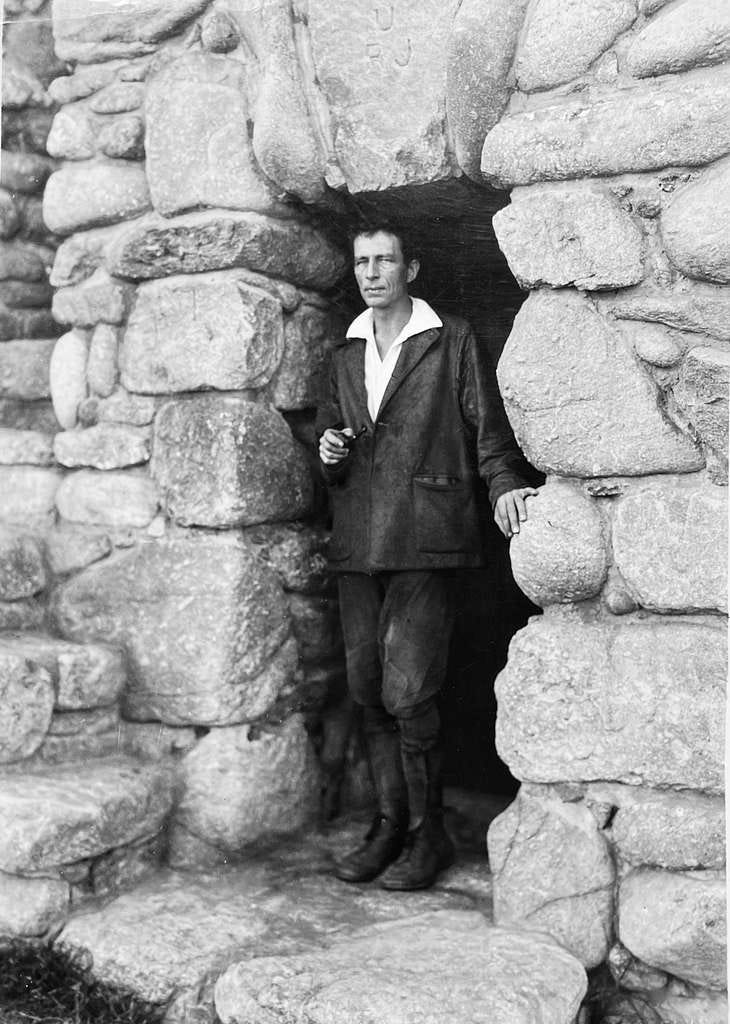

The skeletal metaphor of my experience is not far from Jeffers’ own poetic conception. He wrote of Tor House, “I am heaping the bones of the old mother / To build us a hold against the host of the air.” These bones, for both Tor House and Hawk Tower, are massive. At one point Jeffers used a wheelbarrow to transport them, but the handles broke under the strain of the load. So, he adopted a more primitive technique. He began rolling the stones, end over end, along California’s Carmel shoreline and up the hill to their home. He would often, his son Garth recounts, do this work at night. Was it because some stones were not technically his property? Was he afraid of being reprimanded? I don’t think so. I’d bet that he preferred the night for its solitude. His sinewy figure, illuminated by the reflection of the moon, was seen only by the silent stars and crashing breakers. Not to mention, he saved his afternoons for stone cutting and construction, no time for rolling bones. The house’s cornerstone he named “Thuban,” the ancient north star that guided the Egyptians while they constructed the pyramids. It was an apt name; his work was much closer to the Egyptians’ than to that of the contractors building the multi-million dollar mansions that now surround his property.

Jeffers’ poetic voice, in many ways, matches the roughness and density of stone. From early in his career, he promised himself that he would tell no lies in verse (unlike Shakespeare and Homer, whom he said “flattered the race!”). Although this duty to the truth sounds direct, Jeffers recognized the countless ways we compromise our art: “If we alter thought or expression for any of the hundred reasons: in order to seem original, or to seem sophisticated, or to conform to a fashion, or to startle the citizenry, or because we fancy ourselves decadent, or merely to avoid commonplace: for whatever reason we alter them, for that reason they are made false.” This poetic commitment was foundational for Jeffers’ aesthetic vision. He would pursue and pronounce un-altered truths, even if they were unpopular.

In this pursuit, he turned to the “permanent things” of the natural world. Ignoring the fashions and controversies of the modern moment (such transient subjects were for prose, he thought), Jeffers turned to the ecology of the Pacific coastline. The surf, stones, and birds became his subjects, even human passions, such as love and violence. These were realities that were constant and recurring. Jeffers writes, “Poetry cannot speak without remembering the turns of the sun and moon, and the rhythm of the ocean, and the recurrence of human generations, the returning waves of life and death.” The poet could express these truths across millennia. Such durability was Jeffers’ metric for the great poet, which he outlined in his essay “Poetry, Góngorism, and a Thousand Years.” To build lasting poetry, one must use lasting materials.

These materials, however, were often like his stones, rough and abrasive. In Jeffers’ verse, we encounter both gentle images of nature and terrifying visions of catastrophe. We receive glimpses of life, uncensored of their uncomfortable realities. In “Hungerfield,” he writes, “The poets who sing of life without / remembering its agony / Are fools or liars.” A holistic vision of life must integrate these painful truths. Jeffers opposed the humanistic egoism and self-importance that would minimize or erase such realities. The roughness of his verse is aimed against such inward turning (incurvatus in se), admonishing us to “uncenter our minds” and “unhumanize our views a little.” These poetic depictions are in direct opposition to the smooth aesthetics that modernity and technology advertise. In his book Saving Beauty, the philosopher Byung-Chul Han helpfully notes such contrast: “Natural beauty is opposed to digital beauty. In digital beauty the negativity of the other is entirely removed. It is therefore perfectly smooth.” In Jeffers’ verse, we are not given the luxury of ignoring the other. The other is overwhelming, outreaching, and eclipsing the human presence. We are not in control, exercising a smooth dictatorship over our screen world; we are pressed, face to face, with a world that is mysterious and uncontrollable.

We notice that Jeffers’ stone masonry and artistry were deeply aligned. Poetic material must be permanent like granite and true like a keystone, holding an arch together beneath tons of stone. This aesthetic theory distanced him from (much of) the poetry that dominated the early twentieth century. He saw the progress of Modernism, from Mallarmé on, as an “innovation by amputation,” a stripping away of poetic qualities. He writes,

It [poetry] was becoming slight and fantastic, abstract, unreal, eccentric; and was not even saving its soul, for these are generally anti-poetic qualities. It must reclaim substance and sense, and physical and psychological reality. This feeling has been basic in my mind since then. It led me to write narrative poetry, and to draw subjects from contemporary life; to present aspects of life that modern poetry had generally avoided; and to attempt the expression of philosophical and scientific ideas in verse. It was not in my mind to open new fields for poetry, but only to reclaim old freedoms.

Importantly, Jeffers’ aesthetic vision not only commits to “permanent things,” but it also resolves to take a stand, to say something with “substance and sense.” If the poet is called to tell the truth, the truth ought to be something that the reader can recognize and contemplate. In other words, a poem should have a perspective, a position toward the world that does not continually obfuscate and alienate. This commitment does not endorse didacticism but courage. It demands the poet step forth and tell us something true about the world, something that might invite disagreement or impinge on our comfort. This stepping forth can be dangerous for one’s literary reputation, and one can of course misstep. Unflinching in his cosmic view of world affairs, Jeffers’ apolitical, polemical turn during World War II damaged his reputation (though the relationship between his politics and literary decline tends to be overemphasized). Jeffers’ later unwillingness to accommodate public opinion was clearly an extension of his earlier poetic commitments.

When I emerged from the staircase, I exhaled and stood quietly. Above me, a taxidermy hawk stretched out its wings, as if offering some post-mortem benediction. I opened the entry door and sat down at Jeffers’ desk. The warmth of the sunlight touched the stone walls around me. I heard the distant whoosh of the surf, crashing against its long-acquainted terminus. I watched the same blue horizon, blurred between Pacific and sky, that Jeffers watched through the same window. I settled down to work. Perhaps, I could write something true.

Carter Davis Johnson is a Ph.D. candidate in English at the University of Kentucky. Earlier this year, he was awarded a Tor House Fellowship. This fellowship involved a two-week residency at Robinson Jeffers' house (Tor House) in Carmel, California. During that time, he worked on his dissertation, which explores the environmental philosophy of John Steinbeck, Robinson Jeffers, and Jack London. His work on Jeffers attempts to reframe the poet's work and legacy by approaching Jeffers' philosophy through a phenomenological lens. He writes a regular substack titled Dwelling.

—

Robinson Jeffers, “To the Stone-Cutters”

Stone-cutters fighting time with marble, you foredefeated Challengers of oblivion Eat cynical earnings, knowing rock splits, records fall down, The square-limbed Roman letters Scale in the thaws, wear in the rain. The poet as well Builds his monument mockingly; For man will be blotted out, the blithe earth die, the brave sun Die blind and blacken to the heart: Yet stones have stood for a thousand years, and pained thoughts found The honey of peace in old poems.