A Review of If Nothing by Matthew Nienow

Review by Carla Sarett

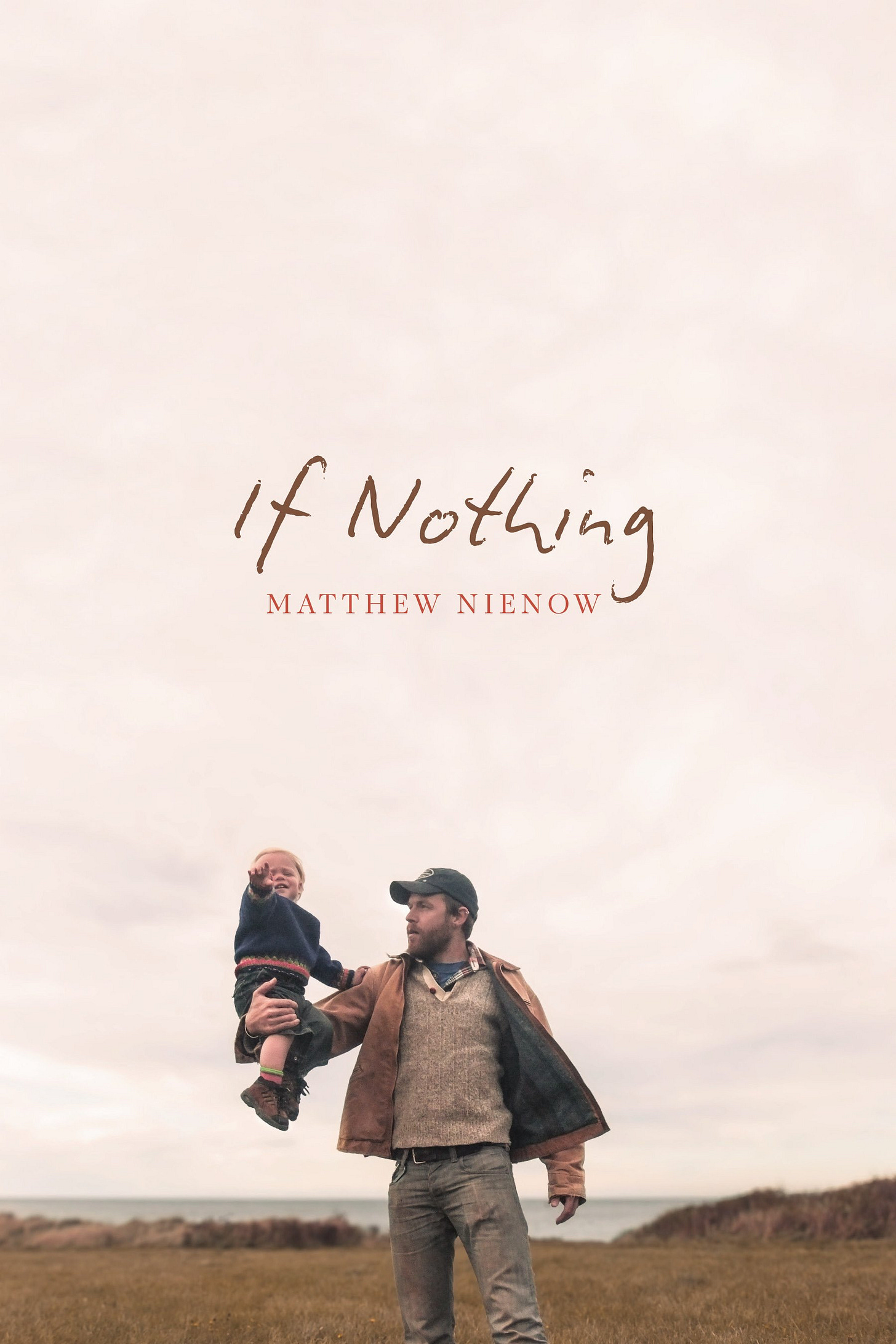

Matthew Nienow, If Nothing. Alice James Books, 2025.

Review by Carla Sarett

Many of us have been touched, indirectly or directly, by the scourge of addiction. A few poets (e.g., Joan Kwon Glass in If Rust Can Grow on the Moon) have written about their own addiction/recovery. Matthew Nienow’s new collection, If Nothing, is a brave entry into this territory. I fell in love with some of these poems at a reading, and on the page, they’re just as exciting.

I think we sense when poems aren’t just a luxury or elegant wordplay—there’s a special indefinable tension. The poems in In Nothing engage in a hard-earned dialogue with one another, and so, the words deepen and change. Conversation between poems isn’t something I demand of poetry collections, but it’s thrilling when it works. The “nothing” of the title moves from absence (of drink) to presence (stillness). The book takes its epigraph from José Saramago: "Inside us there is something [with] no name, that something is what we are." It’s the moment when

After years of binge my hunger

was suddenly gone I became still

for three whole minutes during which

a curt north wind dusted my sills. Still “for three whole minutes”—we have the start of recovery in a nutshell. It’s just a start, but it’s a real start. Yet we also have this tough philosophical question (from “The Return”) about “nothing” versus nihilism (as someone who meditates, I appreciate his distinction):

How does one aim

toward nothing

without tripping

into nihilism?

I banished the drink

in order to live.

I returned

to myself

by making room

for nothing.The path to recovery, in Nienow’s case, is both tangled and simple: on one hand, his weaknesses and fears, and on the other, family and love. In one poem he makes the lovely confession of a father: “Had I been childless, nothing / would have called me from the edge.”. In “For What It’s Worth,” he says, “I’d repeat my sons exactly / as they are, even the one / with the now blue hair still asleep / at the foot of my bed. I’d repeat”. (Somehow, that sleeping blue-haired kid feels just right.)

“Useless Prayer” (one of my favorites in the collection) exemplifies the poet’s bone-dry humor and narrative precision; in spare couplets, he wrestles with his “Lord- of-how-time flies” and “Lord of the sour stomach” and “Lord of my last dollar” through days “drawn like a cell.” The rhyming (sync/drink/dark) is both playful and deadly in these lines:

like the voices of angels, un- intelligible, I fold my hands together in the sign of prayer & begin, O Lord of how-time-flies swatting days down from the calendar, each day drawn like a cell & with bars to keep who's boss known, Lord of the sour stomach & slow walk to the grease joint burger stand to get a dose of dopamine, my brain in sync with the flickering fluorescents in the gas station coolers, the beer just below room temp — O Lord of my last dollar, I need a longer drink. I'd close my eyes for good, Lord, but someone has been tampering with the dark

The “useless” prayer concludes with the poet’s desire to “close my eyes for good” only to find (in a single line, divorced from the safe container of a couplet): “someone has been tampering with the dark.”

The opening poem, “On the Condition of Being Born,” dives into the murky heart of “the dark,” asking us “to stop pretending” that we are “separate” from the ground, “to stop pretending you didn't / come from it and won't go back, eyes open / or closed, thinking or not.” The lines of this poem feel song-like—Nienow was a musician, and continued to write songs even when he wasn’t writing poems. He uses form when he needs it. (He’s also terrific with prose poems.) In an interview with Only Poems, he says:

As I revise, I'm asking the poem on the page to be congruent with the tone and cadence of the poem's energy and spirit. Is a couplet more like a psalm or prayer? A quatrain more narrative? Rather than trying to control the poem, I do my best to listen to the sound that is made through my particular instrument. Some of these songs I nod my head to in clear understanding. Others, I cock my head to the side, curious about a mystery I can't or maybe don't want to solve.

The ghazal, in particular, is used to great effect in this collection. Ghazals can occasionally feel (to my ears at least) forced and overly mannered; but in this poet’s hands, the form’s repetition feels inevitable, and meshes almost magically with his themes of revisiting/regretting his past. Take the beautiful “Ghazal of Lost Years.” The words “letting go” acquire painful associations as the poem moves from the birth of two sons to a father who “numbed the years.”

Out of the dream, we made two sons and learned that love was letting go,

a life made up of days, of longer hours, somehow letting minutes go

to ache for sleep or the chance to read a book or meet a friend to talk

about what was most alive in the middle years, letting go

of our dreams, somehow looking back upon a sheaf of pages scattering in

the wind,

hurts often brighter than the joys, especially for us who numbed the

years, letting go

of first steps and picture books, who cooed lullabies to our young, thick-

tongued,

slurring love in a musk of booze, for us who seemed to think that letting

goIt’s a lot to have lost—this loss (of memory) seems as painful as a death. But Nienow’s final line admits “the past cannot be owned”— and so he must “let go” of mistakes and mangled opportunities. No one else can do this for him; these poems are free of adolescent recrimination. There is not a single petty or small-minded line in any of these poems in If Nothing. Nienow writes: “I stopped / pretending the word was to blame / I was inside with no story / to save me from myself.” The “story” is the fodder of talk show confessions (bad parents, bad schools, bad job, bad world)—and Nienow has become a grown-up. (In his interview with Only Poems, he describes his journey as one of “healthy masculinity.”)

Nienow’s poems confront the reality of being a drunk without vulgarity—we get the point without too much piss and vomit. In a prose poem about his son, “Dusk Loop,” he relives moments when he is “always performing some act of cruelty, always hearing your confused sad cry.” He knows, “No apology will ever be enough.” And in the next poem, he demands what we all must demand of ourselves: “Earn your share of love.” In Apologia, he writes of “carving my apology in stone.” And his poems make me believe him.

The poems insist that nothing should be prettified: “This is not about beauty.” But with poetry, this is only half-true. Beauty may not be the point, but many of the poems in If Nothing are downright gorgeous—it’s the nature of the beast. The concluding poem, “And Then,” sums up the idea of starting anew, armed with the knowledge of past mistakes. The poem ends with these spare, intense (yes, beautiful) lines:

I had lived so long

in the fabric,

I thought it my skin.

I had forgotten

how new

anyone forgiven

can become.The sounds of skin/forgotten/forgiven wonderfully echo the dialogue we have witnessed—before our eyes, the poet has become new. I could sense, as I seldom do, a writer solving his own mysteries through poetry itself. I suppose that is what is called healing. All I could do after finishing If Nothing was to read it again, then again.

Carla Sarett is a contributing editor at New Verse Review. She writes poetry, fiction and, occasionally, essays. She has been nominated for the Pushcart, Best American Essays, Best Microfictions, and Best of the Net. She has published one full-length collection, She Has Visions (Main Street Rag, 2022) and two chapbooks, including My Family Was Like a Russian Novel (Plan B, 2023). Carla has a PhD from University of Pennsylvania and is based in San Francisco.

Thanks for this thoughtful review -- I would not have caught this collection of poetry, but now I will seek it out!