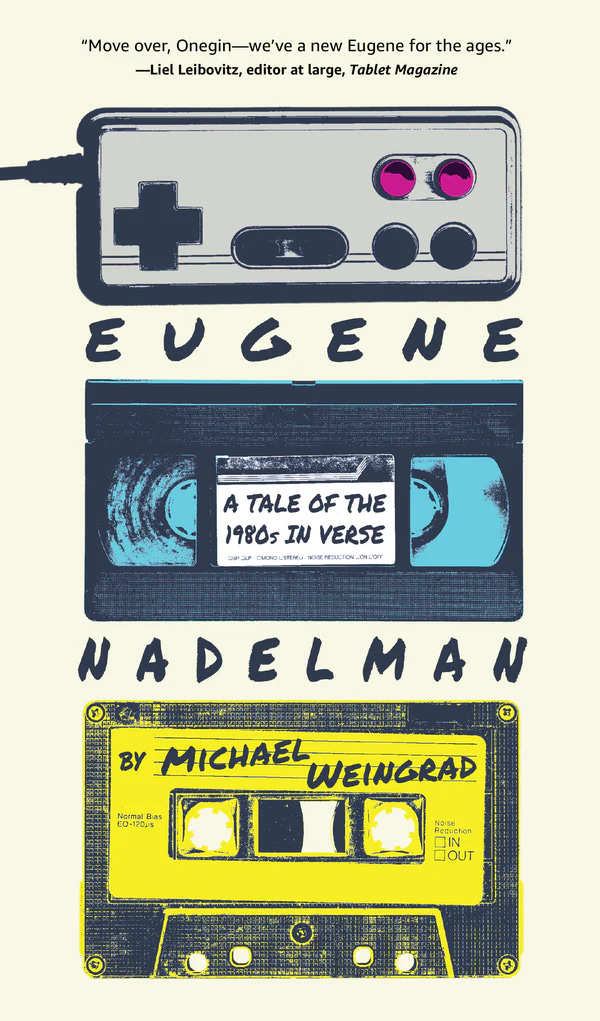

Michael Weingrad, Eugene Nadelman: A Tale of the 1980s in Verse. Paul Dry Books, 2024.

Review by Jonathan Geltner

Michael Weingrad’s novel in verse, Eugene Nadelman, is an achievement both in and exceeding its genre. What exactly is that genre?

Alexander Pushkin’s novel in verse Eugene Onegin is perhaps not as widely read today among English-speakers as it once was. That’s a shame, since it’s a wonderful story, mixing the elegiac and comic, largely by way of its poetic form. That other Eugene is the explicit model for the shorter but only seemingly less ambitious Eugene Nadelman. At one point the poet calls his work a “rendition” of Pushkin’s poem. The structural and thematic similarities are sufficient to warrant that description, but I don’t want to obscure the originality of Eugene Nadelman.

Onegin is a tragedy: the story of a jaded young man who accidentally kills his only friend in a duel, then loses the potential love of his life as a consequence. The tale is presented through the narrator’s persona, which asserts itself throughout the poem. There are, however, many comic asides and digressions, and the overall rueful, elegiac tone does not exclude healthy doses of mirth and satire.

Nadelman adheres closely to Pushkin’s poetic form. The story is set in 1982-1983 and follows a protagonist slightly younger than Onegin, a Jewish guy navigating the awkwardness and revelations of his fifteenth year as they are formed by fantasy, ethnic and religious identity, and the rise and fall of adolescent passion. Pushkin’s nearest cousin in English (and his inspiration) was Lord Byron, and the jocular yet pathetic spirit of that poet presides over Weingrad’s Eugene as well.

So, the first thing we check for is ridiculous rhyming and diction. Outrageous rhymes. Rhymes and word choice that make me guffaw in public. Of such Nadelman provides a judicious amount—not too much and not too little, e.g.:

A beaker was to blame for Tristan’s

Untimely rush toward nonexistence. (I.41)Notice, by the way, that this poem is in the proper tetrameter. The rhyming and diction can get far sillier. Using Tristan in a rhyme is merely funny. We need, however, to see something absurd. Weingrad delivers. He will use the word “eructed” in a rhyme, and the phrase “tagged out at third” for a rhyme in a stanza that is not describing a baseball game. But I’m just getting started. You haven’t seen insane rhyme until you’ve seen Dungeons & Dragons rhyme:

…And that’s not all: a +2

Shield, elven cloak and boots, a staff

Of healing, vorpal sword, and half

A dozen magic arrows. Just to

Be clear, not all are satisfied:

Poor Hal—or was it Herman?—died.There are more than fifteen stanzas describing a session of the role-playing game. Later on the eponymous hero will fight another battle in the game against his friend, thus giving a “rendition” of the duel in Pushkin’s poem. I may, as the author of a novel in which a D&D campaign is played, be a bit biased here, but I’m inclined to call this mise-en-scène a rare achievement.

But it’s something which may become more common, perhaps in time even rising to the level of trope. The game, and fantasy generally, is so popular now—and not just popular but actually sort of prestigious. When our hero Nadelman and his friends play it in 1982, though, it’s anything but prestigious. I’ll come back to this sort of technological irony, as I might call it, in thinking about this poem’s nostalgia.

One of the pleasures of silly rhyming—a pleasure already on display in the example that alludes to the medieval epic of starcrossed lovers, Tristan and Isolde—is discovering serious matter beneath phonetic and syntactic whimsy. The weight of the matter is more obvious here, where the rhyme “try on / Zion” is perhaps not ridiculous so much as opportune, as we learn something of both the inner life and the family life of our teenage protagonist:

Eugene is trying to decipher

The true significance of life, or

At least the day’s events. It seems

To him the telos of his dreams,

The crown that he is meant to try on,

Is love. The kiss that he received

Has with some alchemy conceived

A goal equivalent to Zion

For Cousin Ellen…The poet can use rhyme to make surprising combinations like “azalea / paraphernalia” and stark juxtapositions, as in “ills // daffodils”:

The spring can now proceed serenely

And Philadelphia puts on queenly

Adornments: cherry blossoms, pink

And fresh, preside above the stink

Of uncollected trash; azalea

And rhododendron buds

Unfold beneath the April scuds,

And broken glass, drug paraphernalia,

And other signs of social ills

Are scattered among daffodils. And here we have a perfect combination of comic diction and silly rhyme with two other related but distinct aspects of Nadelman, period reference and allusion:

… Sorry, Rutger Hauer,

The movie choices of our swain

Are lost this time, like tears in rain.Pushkin’s poem is full of allusion—that is, unacknowledged quotation or obscured reference—as Nadelman alludes here to the film Blade Runner, released in 1982. But Onegin does not go out of its way to supply period references. Pushkin’s poem is full of natural description and a kind of generalized countryside contrasted with glitzy Moscow, but in its canonical form does not emphasize place, as in the above description of Philadelphia and many others like it (sometimes more detailed) in Nadelman.

Reference and allusion in Nadelman can be literary or high-brow but most commonly these means of expanding the scope of a work gesture to the popular music and technology of the time. In other words, reference and allusion are not merely means of showing off but ingredient to the poem’s larger project of nostalgia. Of course, allusion is also a legitimate pleasure in its own right. When deft, it passes so smoothly that it is no hindrance to the reader who doesn’t “get it” but gives a little thrill to the one who does.

Some of the more recondite allusions I caught are:

To fantasy author Gene Wolfe’s character Severian—brand new in the early 80s—in the name of a D&D character;

Any reference to D&D, such as the previously quoted “+2 / Shield” or the names of wizards from the Grayhawk campaign, etc;

The phrase “Reach out and touch someone,” which was a phrase in an AT&T commercial;

To the second volume of Proust’s personal epic, also an elegiac work, particularly in regard to the kind of young love under consideration in Nadelman.

But what gives the poem gravity? For gravity it has, though there is no tragic death as in Pushkin’s model. There is an overall balance and plan to the poem that satisfies and marks it as a mature work of art. I’m thinking primarily of the winter and summer seasons facing off against each other in the form of the apostrophe to the poet’s brother, which reminisces about a long-ago snow day, and the final canto, set mostly in a summer camp called Paradise. But in design alone we don’t find gravity, pathos.

I submit that the significance of Eugene Nadelman comes through clearly and in its entirety in lines like this, in which the poet’s acumen viz line, diction, rhyme, etc is again on display:

And yet this festive, endocrinal

Display, had I a Polaroid

To show today, would not avoid

Appearing obsolete as vinyl

And dated as the dial tone

When picking up a land-line phone. There is a new kind of nostalgia apparent today, as those of us born between the late 60s and early 80s try to make our contribution to humane letters. We are the last generation to recall life in the Analog World. We remember the Cold War, and first love (the chief subject of Nadelman) before the Internet. We remember how the world felt before it was mediated (even Dungeons & Dragons!) by screens. And we are doing everything in our power to get that world down on paper—or, indeed, on a screen—before the chance and the memory is lost (like tears in rain?). Pushkin’s poem is elegiac—but that tone comes mostly from the poet’s mourning his lost youth. It is not a historical sense of loss, because in Pushkin’s day you could not write a historical novel simply by writing about the period of your own youth. Now you can.

Far more I could say about Eugene Nadelman, but my enthusiasm has sent me far past my word limit and made a mess for the editor—a mess I am only making worse with each next word. And yet, I feel compelled to conclude by admitting that I have written this review in Arlin’s Bar and Grill on Ludlow Avenue in Cincinnati, Ohio—which is, to invoke one of the presiding sentiments of Weingrad’s Eugene, my Philadelphia: sweet, desultory home place from which life has separated me. This bar is one of my few old haunts that is unchanged from how it was decades ago. They still, in this fearful and sterile decade, reuse your pint glass. I know of no better environs in which I could have written about Weingrad’s delightful, tearful poem.

This review will also appear in NVR 1.1: Summer 2024

Jonathan Geltner is the translator of Paul Claudel’s Five Great Odes (Angelico Press) and the author of Absolute Music: A Novel (Slant Books). With his wife and young children, he lives in southeastern Michigan, where he teaches creative writing, swings a sword, cycles, and plays D&D.